The Anatomy Of A Disaster

1917 Halifax Explosion Blast Cloud Photographs, Location, Description and Reference Numbers:

A Blast Cloud Photograph by Victor Magnus

1917 Halifax Explosion Blast Cloud Photographs, Location, Description and Reference Numbers:

A Blast Cloud Photograph by Victor Magnus

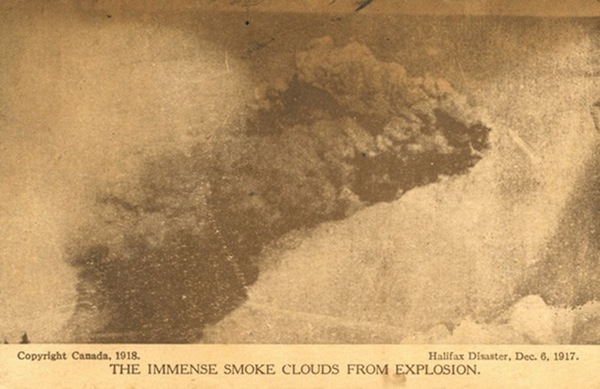

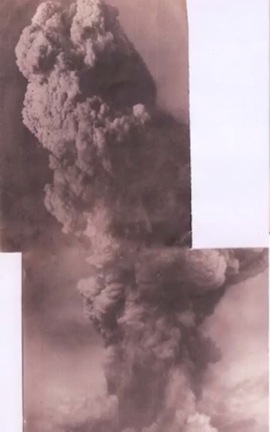

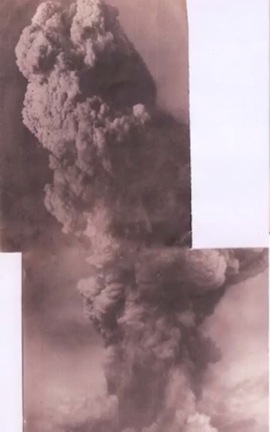

The photograph below is documented as having been taken by Sub-Lt. Victor Montague Magnus aboard HMS Changuinola on the morning of 6 December 1917, approximately three-quarters of a mile from the blast. The image was not in the group published by the Daily Mail in 2014 but was first seen in a YouTube video of Magnus's photo collection (now unavailable). This copy of the original image was obtained from Magnus's great-grandson, Damian Saunders, for use in an article in Queen's Quarterly, no. 124, vol. 4, 2018 by Ken Cuthbertson - "The Horrors of the Halifax Explosion: Long-lost photographs of Canada's worst disaster have recently been uncovered, giving us an extraordinary view of the terrible events that unfolded 101 years ago." Ken has kindly provided the image.

It appears that for this image, Magnus used a shorter focal length to get the wide shot. For most of his other images below, he would have extended the bellows on his camera to achieve a longer focal length so to capture more detail but within less area.

* * *

The RGS Photograph Debunked

It appears that for this image, Magnus used a shorter focal length to get the wide shot. For most of his other images below, he would have extended the bellows on his camera to achieve a longer focal length so to capture more detail but within less area.

* * *

The RGS Photograph Debunked

Recently, CBC forwarded a digital photo for the purpose of analysis and verification, purportedly taken by someone with the initials R.G.S.. After a month or so of research, I concluded that the enigmatic and surreal image depicts a scenario that frankly goes very much against most known facts about the aftermath of the explosion. The photograph's provenance was credibly linked to Mate Reginald Garnet Stevens who was assigned to HMCS Acadia at the time of the explosion. Below is a CBC news story from July 2020.

However, features within this photo bear a very close resemblance to those in the above snapshot taken by Victor Magus. These similarities have cast doubt on the legitimacy of the RGS image. I am in agreement with historian/geophysicist Alan Ruffman, who pointed out the that these undeniable similarities cannot be ignored.

The RGS image completely distorts perceptions of actual distance. The Magnus photograph was taken three-quarters of a mile away from the explosion, but the RGS image makes it look like the blast cloud sits scant yards behind the vessel. I have provided a blast cloud comparisons page. Also, the button below will open a new window so the photographs above can be flipped back and forth by moving your cursor on and off the image to demonstrate that the Magnus and RGS photos contain identical elements. The composite is a 50% opacity Magnus image with the necessary angular adjustments. The proportions were constrained. Were it not for the existence of the 100% documented Victor Magnus photograph, no one would be the wiser. As the composite shows, the features appear identical enough to conclude the RGS photograph is not a true representation of a moment in time from the Halifax Explosion.

This image is a WWI composite photograph, a combination of two or more negatives. This type of photography was quite common in this era. Though controversial, the idea was to portray events using multiple negatives to make the final result more dramatic and provocative. The work of Australian WWI photographer Frank Hurley is the epitome of this method of constructing images.

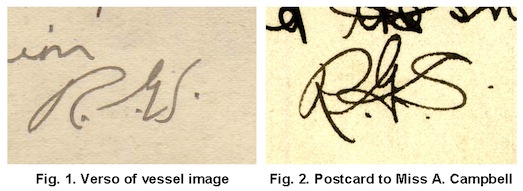

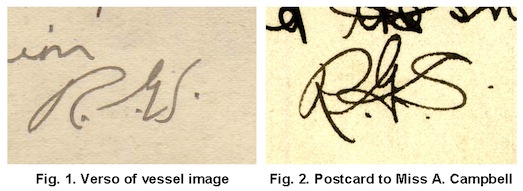

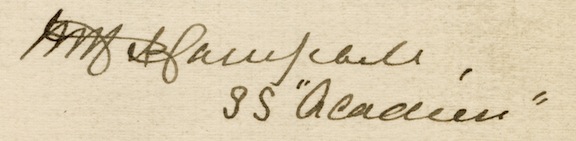

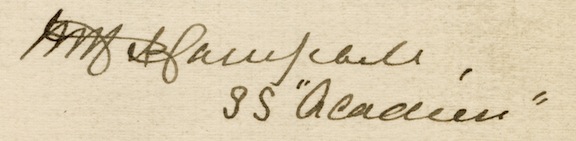

All of this really comes a no surprise considering the continuous line of red flags the image presented during the entire process of trying to establish its provenance. I do not believe the photograph was meant for the marketplace and therefore, its creation can be viewed as a possible lark or an experiment by an amateur photographer. Mate Stevens likely had nothing to do with the creation of the image. As shown below, the initials on the verso of the RGS image and his initials from a personal postcard from HMCS Algerine to Miss A. Campbell are noticeably dissimilar. (see below)

"There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn't true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true." - Soren Kierkegaard

This image is a WWI composite photograph, a combination of two or more negatives. This type of photography was quite common in this era. Though controversial, the idea was to portray events using multiple negatives to make the final result more dramatic and provocative. The work of Australian WWI photographer Frank Hurley is the epitome of this method of constructing images.

All of this really comes a no surprise considering the continuous line of red flags the image presented during the entire process of trying to establish its provenance. I do not believe the photograph was meant for the marketplace and therefore, its creation can be viewed as a possible lark or an experiment by an amateur photographer. Mate Stevens likely had nothing to do with the creation of the image. As shown below, the initials on the verso of the RGS image and his initials from a personal postcard from HMCS Algerine to Miss A. Campbell are noticeably dissimilar. (see below)

"There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn't true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true." - Soren Kierkegaard

Read my article "The RGS Photograph: An Evaluation of a Purported 1917 Halifax Explosion Artifact" in Volume XXXVII Number 1 Winter 2021 edition of Argonauta, the Newsletter of The Canadian Nautical Research Society / Societe canadienne pour la recherche nautique.

* * *

* * *

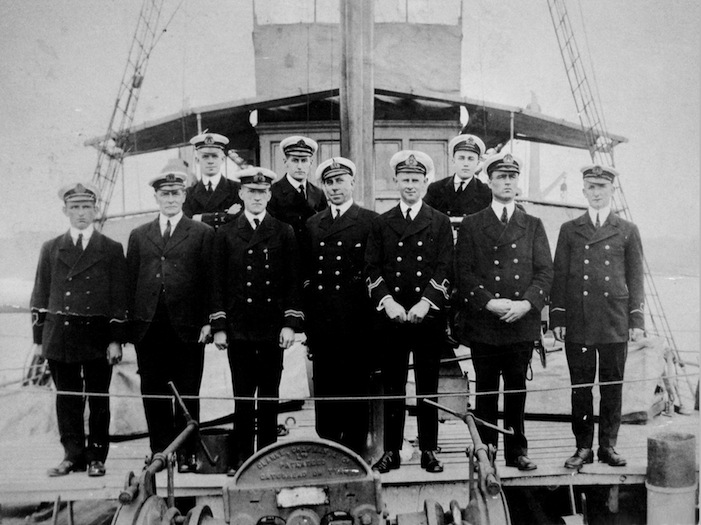

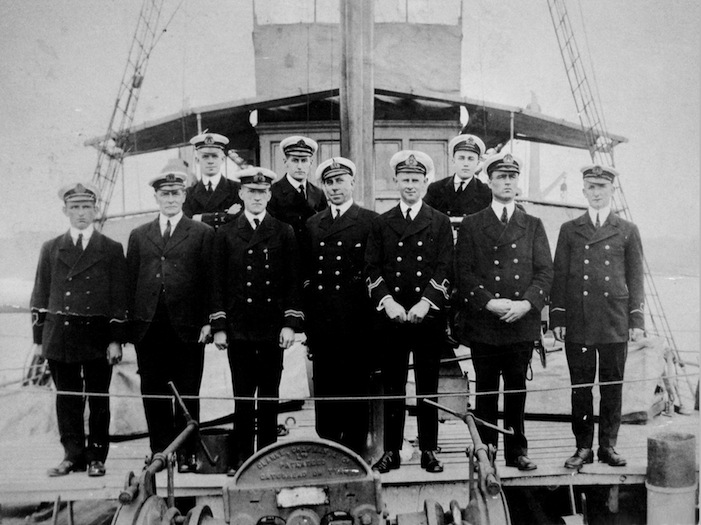

Officers and Men of HMCS Acadia 1917

Back Row (l-r): John Davidson, Cameron Duncan, George Peters

Front Row (l-r): Claris Peter Bourgeois, William Alfred Robson, Frederick A. Simpson,

Herbert H. DeLally Wood (Commanding Officer), George Maude, Joseph M. Murphy, William Ralph Chandler

Captain Frederick Claude Coote Pasco is seated fourth from the left in the front row.

(The two photographs above were likely taken at Lansdowne, Cape Breton in September 1917)

(standing l-r) Mates: Walter C. C. Duncan, William R. Chandler, James S. Dresser, Frank Bertram Foulds, Claris Peter Bourgeois,

Reginald Garnet Stevens, Elmo L. Ashbourne, (seated l-r) Lieutenants: Herbert H. DeLally Wood, George Maude

(Photograph taken between 21 and 29 November 1917)

* * *

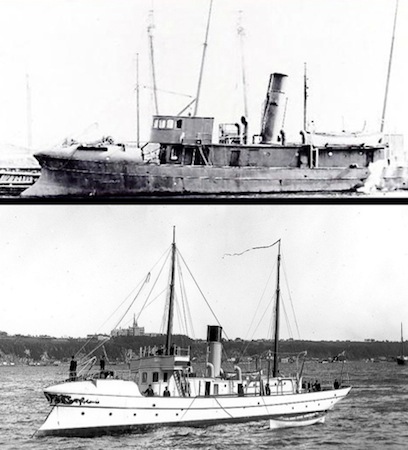

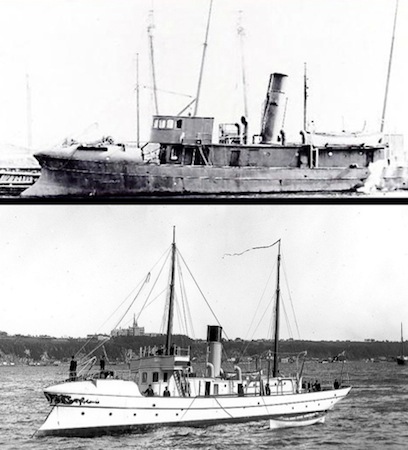

SS Senlac / SS Acadien

Back Row (l-r): John Davidson, Cameron Duncan, George Peters

Front Row (l-r): Claris Peter Bourgeois, William Alfred Robson, Frederick A. Simpson,

Herbert H. DeLally Wood (Commanding Officer), George Maude, Joseph M. Murphy, William Ralph Chandler

Captain Frederick Claude Coote Pasco is seated fourth from the left in the front row.

(The two photographs above were likely taken at Lansdowne, Cape Breton in September 1917)

(standing l-r) Mates: Walter C. C. Duncan, William R. Chandler, James S. Dresser, Frank Bertram Foulds, Claris Peter Bourgeois,

Reginald Garnet Stevens, Elmo L. Ashbourne, (seated l-r) Lieutenants: Herbert H. DeLally Wood, George Maude

(Photograph taken between 21 and 29 November 1917)

* * *

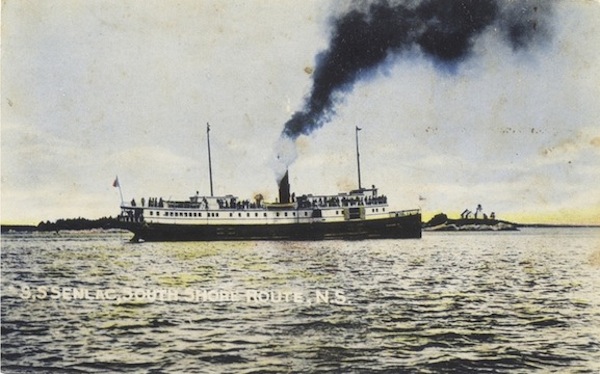

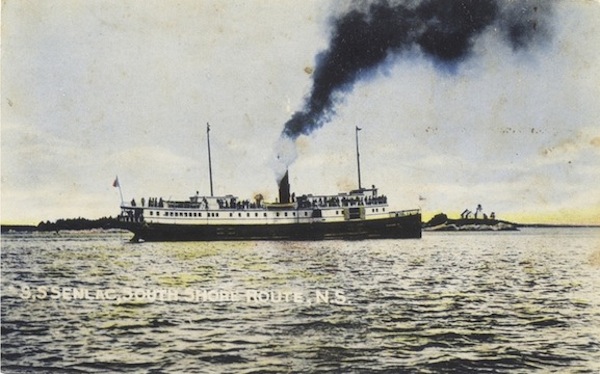

SS Senlac / SS Acadien

SS Acadien was steaming into Halifax Harbour on the morning of 6 December 1917 when the explosion took place. The ship was approximately 15 miles from port when her master, Captain W. M. A. Campbell, took a sextant reading to determine the height of the fire emanating from the top of the blast cloud. Acadien was scheduled to arrive at Halifax at noon but there is no known record of her having entered the port.

Below: A colorized postcard showing Senlac on her South Shore, N. S. route.

Many authors and historians often confuse Acadien with another vessel when referring to Captain Campbell's ship. Probably one of the first was Michael J. Bird, wherein the prologue (p. 10) of his book, The Town That Died (1962, G. P Putnam's Sons, New York), the author refers to this ship as the Acadian. There was indeed a steel-hulled vessel, Acadian (1908, 2,035 grt), of the Canadian Steamship Lines - a Great Lakes ship torpedoed and sunk in 1918 - but this was not Captain Campbell's much smaller, wooden vessel (1916, 707 grt). In his written account to Archibald MacMechan, Campbell signed his name and clearly wrote SS Acadien beneath his signature.

Robin H. Wyllie accurately recounts the ship's history in his article "Maritime Provinces Steam Passenger Vessels," Argonauta Oct., 1993, pp 15-17. The vessel was originally SS Senlac (1904, 615 grt) before being sold to the French government in 1916 following its near-destruction from fire at Sydney Harbour 14 December 1915. Wylie makes no mention of the name change to Acadien within the article proper, though he cites the documentation of Captain Campbell as one of his sources (PANS MG1, vol. 2124 # 178. "Flame Height of the Mount (sic) Blanc Explosion." Undated deposition by Captain Campbell, SS Acadien). The ship is also mentioned on Walter Lewis's website, Maritime History of the Great Lakes on the following page: Senlac (1904). There are several other sources with fact-based information on the vessel.

The name change from Senlac to Acadien likely occurred after the ship was sold to Brister & Co. in Halifax for refurbishment. However, with the establishment of a new route, Captain Campbell became concerned that the ship was not powerful enough for the ice between Louisbourg and her destination. He refused to continue in command after taking Acadien from Halifax to Louisbourg in early 1918. With the ship detained in Cape Breton, the company's agent, Charles Farvaque, accepted an impromptu offer to step in as the ship's master from retired sea captain and Halifax businessman, D. A. Scott. The French Consul, E. La Croix, then accompanied Scott from Halifax to Louisbourg and bade him farewell. After sending word of a safe arrival at Burin, Newfoundland, the steamer set sail two days later for St. Pierre. On Thursday, 21 February 1918, Acadien, Captain Scott, and nine crew members were lost in a powerful gale.*

*Source: St. John's Daily Star, 1918-03-06, page 7, col. 1.

In April of 1918, the previously thought lost ship Acadien was located five miles east of Flat Island, Placentia Bay. Both anchors were out. The stem was underwater and the stern out of the water but the ship had not broken up. A coastal steamer was sent out by the government to inspect the wreck.** What happened to the ship next is unclear. However, according to an article in the Evening Telegram from 1922-08-18, a ship named SS Acadien arrived from St. Pierre the day before and berthed at the Furness Pier.

**Source: St. John's Evening Telegram, 1918-04-15, page 4, col. 2.

Click on the image below to read Captain Campbell's first-hand account.

* * *

The Daily Mirror Images

The name change from Senlac to Acadien likely occurred after the ship was sold to Brister & Co. in Halifax for refurbishment. However, with the establishment of a new route, Captain Campbell became concerned that the ship was not powerful enough for the ice between Louisbourg and her destination. He refused to continue in command after taking Acadien from Halifax to Louisbourg in early 1918. With the ship detained in Cape Breton, the company's agent, Charles Farvaque, accepted an impromptu offer to step in as the ship's master from retired sea captain and Halifax businessman, D. A. Scott. The French Consul, E. La Croix, then accompanied Scott from Halifax to Louisbourg and bade him farewell. After sending word of a safe arrival at Burin, Newfoundland, the steamer set sail two days later for St. Pierre. On Thursday, 21 February 1918, Acadien, Captain Scott, and nine crew members were lost in a powerful gale.*

*Source: St. John's Daily Star, 1918-03-06, page 7, col. 1.

In April of 1918, the previously thought lost ship Acadien was located five miles east of Flat Island, Placentia Bay. Both anchors were out. The stem was underwater and the stern out of the water but the ship had not broken up. A coastal steamer was sent out by the government to inspect the wreck.** What happened to the ship next is unclear. However, according to an article in the Evening Telegram from 1922-08-18, a ship named SS Acadien arrived from St. Pierre the day before and berthed at the Furness Pier.

**Source: St. John's Evening Telegram, 1918-04-15, page 4, col. 2.

Click on the image below to read Captain Campbell's first-hand account.

* * *

The Daily Mirror Images

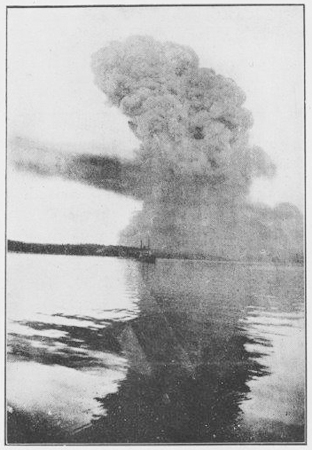

The two images below are from the British newspaper, The Daily Mirror, dated respectively, the 29th and 30th of December 1917. The image on the left is from a ship moored on the western side of Bedford Basin. The vessel is unknown. The most interesting aspect of this image is that there are personnel watching the explosion as it is happening. The angle of the shot is very similar to the U. S. Coast Guard image further down this webpage.

The second image is a rare frontal view of almost the entire blast cloud from the harbour side in its fairly early stages. A touch of colour has been added to the image which has been enhanced to remove a dark line that ran the entire length down the centre of the image. The upper levels of the blast cloud have not yet risen to full height. A bump can be seen forming to right of image where a separate plume erupted within seconds. This arm can be viewed in C. W. Vernon, NARA and Le Mirior photos further down this page.

The photographer and location are unknown but the image looks as though it was taken from a distance of at least one and a half to two miles from the blast - possibly from aboard HMS Highflyer but further research is required.

.jpg)

* * *

HMCS Acadia as a Location for the Photographer of the "Iconic" C. W. Vernon Image

The second image is a rare frontal view of almost the entire blast cloud from the harbour side in its fairly early stages. A touch of colour has been added to the image which has been enhanced to remove a dark line that ran the entire length down the centre of the image. The upper levels of the blast cloud have not yet risen to full height. A bump can be seen forming to right of image where a separate plume erupted within seconds. This arm can be viewed in C. W. Vernon, NARA and Le Mirior photos further down this page.

The photographer and location are unknown but the image looks as though it was taken from a distance of at least one and a half to two miles from the blast - possibly from aboard HMS Highflyer but further research is required.

.jpg)

* * *

HMCS Acadia as a Location for the Photographer of the "Iconic" C. W. Vernon Image

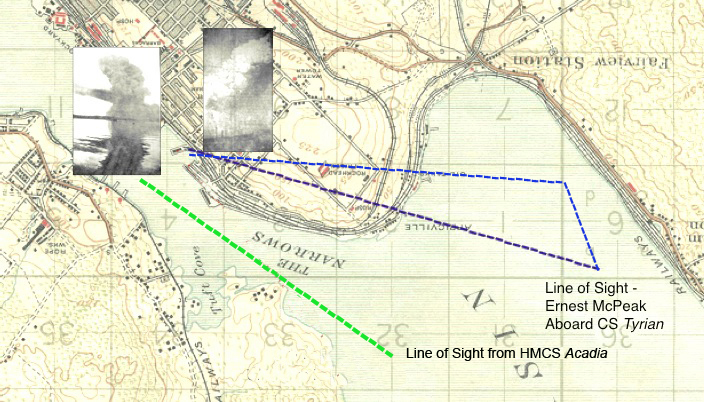

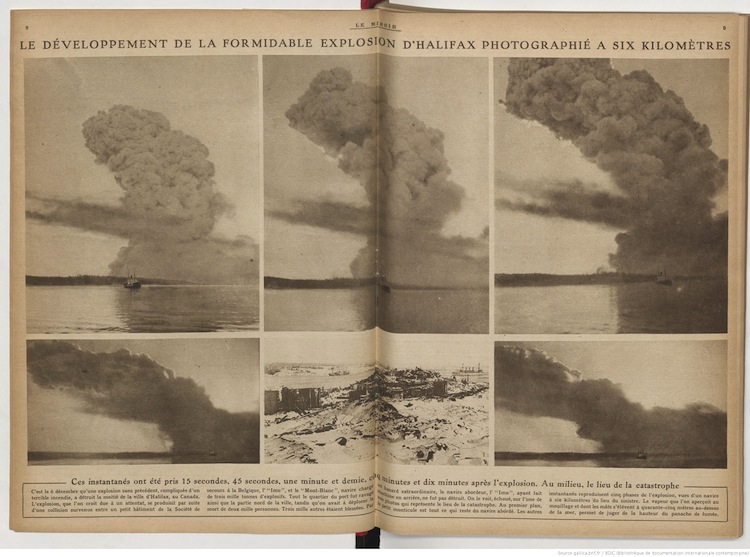

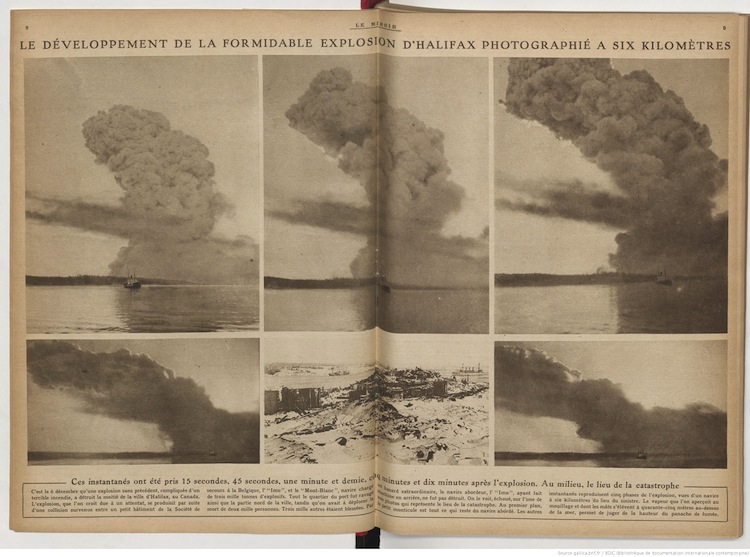

After due consideration and more research of archival photographs as well as in the field, I have updated the origin probabilities of the series of (cropped) five blast cloud images shown in the French publication (January 1918) Le Miroir (below):

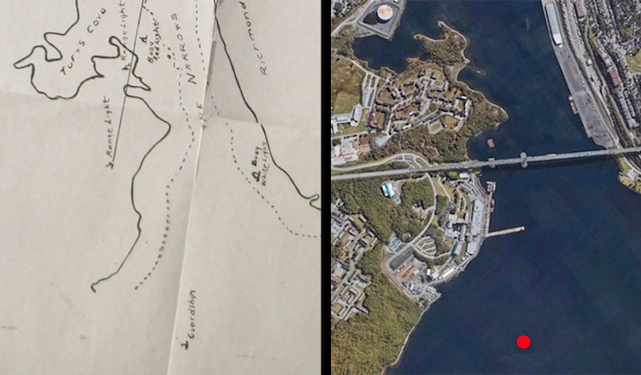

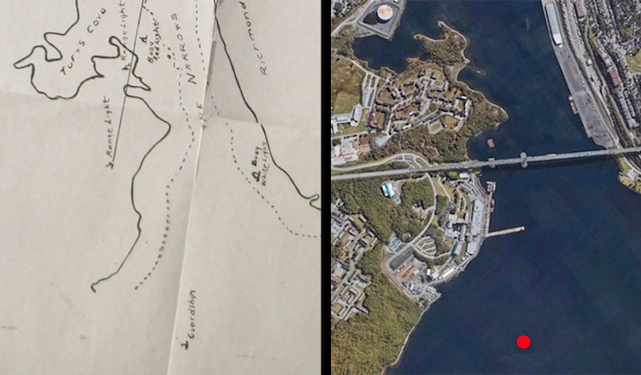

The location of HMCS Acadia in Bedford Basin at the eastern head of the Narrows on 6 December 1917 is conducive to the notion that these photographs were taken from aboard this vessel. The approximate co-ordinates of the guard ship were established via the testimony at the inquiry of one of the British officers aboard, Lieutenant Arthur McKenzie Adams, RNVR, of the Naval Control Office, who confirmed Acadia's location after being shown exhibit M.B.E. 63 while on the stand.

The location of HMCS Acadia in Bedford Basin at the eastern head of the Narrows on 6 December 1917 is conducive to the notion that these photographs were taken from aboard this vessel. The approximate co-ordinates of the guard ship were established via the testimony at the inquiry of one of the British officers aboard, Lieutenant Arthur McKenzie Adams, RNVR, of the Naval Control Office, who confirmed Acadia's location after being shown exhibit M.B.E. 63 while on the stand.

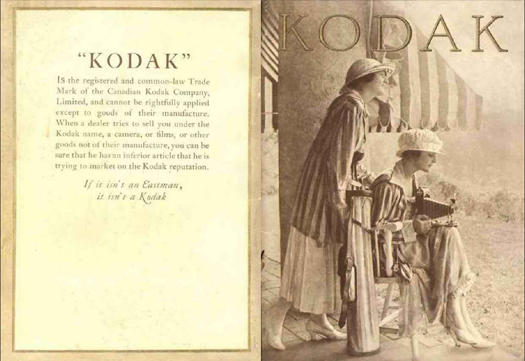

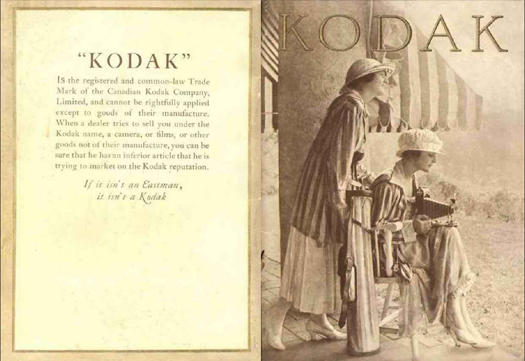

Additionally, the recent emergence of material associated with one of her British complement, Frank Herbert Baker, has contributed to the remote possibility he was the one who photographed these striking images. According to his diary, he and other personnel had been transferred from the examination boat Berthier to Acadia on 4 December, two days before the explosion. The photograph below from 1917, shows Mr. Baker (left) with what appears to be a Model E Kodak camera. However, a good argument against Mr. Baker having been the photographer of these images is that he was still on duty aboard Acadia in Halifax at the time the photographs were published in Le Miroir. Regardless, the evidence points to the photograph having been taken by someone aboard HMCS Acadia.

How these five images ended up in a French periodical and not in Britain so soon after the disaster is not impossible to figure out. At the beginning of WWI, many of the French illustrated press put out a call to photography enthusiasts who were encouraged by photography competitions. In 1915, Le Miroir offered 30,000 francs for "the most striking photograph of the war." which initiated other contests in periodicals throughout the country. Subsequently, Le Miroir offered a weekly contest with prizes up to 1,000 francs.

Acadia may have been a Royal Canadian Navy vessel during the war, but she was manned by Imperial personnel. It follows that a member of the ship's complement returning to Britain may have had the incentive to submit these five photographs.

How these five images ended up in a French periodical and not in Britain so soon after the disaster is not impossible to figure out. At the beginning of WWI, many of the French illustrated press put out a call to photography enthusiasts who were encouraged by photography competitions. In 1915, Le Miroir offered 30,000 francs for "the most striking photograph of the war." which initiated other contests in periodicals throughout the country. Subsequently, Le Miroir offered a weekly contest with prizes up to 1,000 francs.

Acadia may have been a Royal Canadian Navy vessel during the war, but she was manned by Imperial personnel. It follows that a member of the ship's complement returning to Britain may have had the incentive to submit these five photographs.

An acquaintance, Stephen Osler, was kind enough to transport me in his sailboat up to Acadia's position where I took the photograph seen on the right below. The image on the left is the uncropped version of the iconic blast cloud image. After comparing these images, there should be little doubt, if any, that the original blast cloud photographs were taken from the deck of HMCS Acadia.

I have narrowed the possibilities to the ship in the foreground as one of three examination boats that could have been in this position: Curlew, Constance and Speedy II. This conclusion was determined due to the odd shape of the vessel's prow shown in the expanded denigrated image of the vessel (below left). The look of the raised area on the bow suggests the object is a whaleback, a metal covering used to deflect water away from the foredeck. Images of Curlew and Constance (below right) confirm the use of whalebacks and also demonstrate the vessels' unique prow design.

* * *

* * *

Le Miroir Images

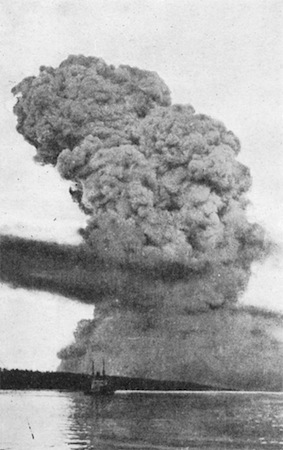

Five blast cloud photographs, one of which is usually referred to as the "iconic" photo, were taken from a French vessel in Bedford Basin. These were originally printed in the 1918/01/13 edition of Le Miroir. The ship from which the images were taken is likely HMCS Acadia, a guard ship moored on the eastern side of Bedford Basin. It should be noted that the "iconic" photo is cropped and not shown in its entirety as published in the 14 February 1918 issue of Church Work and subsequent booklet by C. W. Vernon as shown further down the page. The images are available for viewing in more detail at Gallica.

Rough translation of the accompanying text:

Rough translation of the accompanying text:

"On December 6, an unprecedented explosion, complicated by a terrible fire, destroyed half the city of Halifax, Canada. The explosion, believed to be due to an attack, occurred as a result of an incidental collision between a small vessel of the Belgian Relief Commission, the Imo, and the Mont-Blanc, a ship loaded with three thousand tons of explosives.

The whole quarter of the harbour was ravaged, as well as the northern part of the city, while the deaths of two thousand persons had been reported. Three thousand others were wounded. By an extraordinary chance, the ship colliding, the Imo, having turned back, was not destroyed. One sees it, stranded, in one of our photos which represents the place of the catastrophe.

In the foreground, the small mound is all that remains of the vessel which collided. The other snapshots reproduce five phases of the explosion, seen from a ship six kilometers from the scene of the disaster. The steamship, which is seen at the anchorage, and whose masts are elevated forty-five meters above the sea, makes it possible to judge the height of the plume of smoke."

The whole quarter of the harbour was ravaged, as well as the northern part of the city, while the deaths of two thousand persons had been reported. Three thousand others were wounded. By an extraordinary chance, the ship colliding, the Imo, having turned back, was not destroyed. One sees it, stranded, in one of our photos which represents the place of the catastrophe.

In the foreground, the small mound is all that remains of the vessel which collided. The other snapshots reproduce five phases of the explosion, seen from a ship six kilometers from the scene of the disaster. The steamship, which is seen at the anchorage, and whose masts are elevated forty-five meters above the sea, makes it possible to judge the height of the plume of smoke."

Commentary:

The mention of six kilometres distance is not viable and the height of the masts of the vessel in the foreground would have likely been unknown to the writer. SS Imo never "turned back" and the ship's final position, of course, is not the "the place of the catastrophe." Regarding the middle image, second row, it should be noted that the writer of the article states the wreckage of the destroyed Acadia Sugar Refinery as that of Mont-Blanc. There are no clues as to the sources of the article's misinformation.

Information of the photographic source (Le Miroir) provided by Alan Ruffman with credit to philatelist, Leon Matthys, from Aurora, Ontario for initially finding the file.

Information of the photographic source (Le Miroir) provided by Alan Ruffman with credit to philatelist, Leon Matthys, from Aurora, Ontario for initially finding the file.

* * *

Photographs by Sub-Lt. Victor Magnus, R.N.V.R., HMS Changuinola

Photographs by Sub-Lt. Victor Magnus, R.N.V.R., HMS Changuinola

These previously unseen photographs below (including composite) are from several in the collection of Sub-Lieutenant Victor Montague Magnus, RNVR published by the UK newspaper the Daily Mail in 2014. The images show the blast cloud in its early stages before the animal head configuration rose to the very top of the blast cloud. Magnus was stationed aboard HMS Changuinola, moored in the dockyard. In these rare photographs, the blast cloud is seen from the harbour side of the explosion.

The location of the ship was roughly in midstream, abeam of HMCS Niobe. Looking along a line of sight to the northwest, the top of the blast cloud was pointed to the southeast. The photo above left is true base of the blast cloud and the plume. To the right is the top of the cloud. The image above left, is the bottom of the plume. Below left is a composite of the two photos created by Magnus. On the right is an illustration by E. Mudge-Marriott from Michael Bird's book The Town That Died - completed with some degree of artistic license from the composite. Victor Magus's name appears in the book's acknowledgements.

Another of Magnus's photographs (below left) and the photo to the right are from HMS Changuinola's location looking towards the northwest Halifax shore. Magnus labelled this "Fire at Halifax." Two unidentified vessels are at the left of frame. Without high resolution images to view, identification is impossible. The white then dark smoke in the foreground is from a steamboat off the ship's port side. These appear to be post-explosion as the smoke from the blast cloud has enveloped most of the North End.

Below: Blast cloud images showing almost the same view with only a moment or two in between. Left: From a page of Victor Magnus's photographs donated by a relative. Source: Maritime Museum of the Atlantic - Reference MP 207 1 184 431; Right: A screen grab from the aforementioned YouTube video of the Magnus Collection.

* * *

* * *

The 1918 Canadian Kodak Catalogue

* * *

1917 Halifax Explosion Blast Cloud Photographs

* * *

1917 Halifax Explosion Blast Cloud Photographs

The fire on the Mont Blanc raged between fifteen and twenty minutes before the explosion. The thick smoke from the spilled benzol on deck rose high in the sky and could be seen from a distance. All of these photos are likely post-explosion. Some may also be cropped.

There is cable or rigging of some kind visible in a few of the images. On the day of the explosion, there were a number of ships in Bedford Basin. Within the first few minutes, the fire alone would have already been a significant event. It is not unreasonable to assume that pre-explosion and explosion images, known and unknown, were taken onboard any number of these vessels. By 1917, cameras had evolved to the point where they were fairly compact and easy enough to use quickly. Anyone aboard a ship in Bedford Basin who had a camera would have had a good line of sight to the Narrows but still be far enough away to safely take a photograph of the fire or the explosion.

Photo 1 ended up in the possession of the U. S. Coast Guard which implies that this particular photo was taken from one of their vessels. Photo 3 was taken by Ernest McPeak on Tyrian. A well known cropped version of Photo 4, the main subject of this website, came as an Underwood and Underwood image to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) from the U.S. Records of the War Department General and Special Staff.

There is cable or rigging of some kind visible in a few of the images. On the day of the explosion, there were a number of ships in Bedford Basin. Within the first few minutes, the fire alone would have already been a significant event. It is not unreasonable to assume that pre-explosion and explosion images, known and unknown, were taken onboard any number of these vessels. By 1917, cameras had evolved to the point where they were fairly compact and easy enough to use quickly. Anyone aboard a ship in Bedford Basin who had a camera would have had a good line of sight to the Narrows but still be far enough away to safely take a photograph of the fire or the explosion.

Photo 1 ended up in the possession of the U. S. Coast Guard which implies that this particular photo was taken from one of their vessels. Photo 3 was taken by Ernest McPeak on Tyrian. A well known cropped version of Photo 4, the main subject of this website, came as an Underwood and Underwood image to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) from the U.S. Records of the War Department General and Special Staff.